Taming the Use of Tax Expenditures. Evidence From The Netherlands

Rocus van Opstal | 1 November 2023

Fiscal, Blog | Tags: Parliaments, Tax Expenditures, The Netherlands

This is the first blog from the series on Tax Expenditure Policy Making and the Role of Parliaments.

This summer, the Dutch finance ministry published a report on the effectiveness of the country’s tax expenditures[1]. The verdict on the myriad of deductions, exemptions and further benefits channelled through the tax system was harsh. Only a small share of them was deemed both effective and cost-efficient in supporting the objective they were designed to promote. A significant number was seen as ineffective or inefficient. And for many, the ministry concluded that there is no case for government intervention or that the case is unclear.

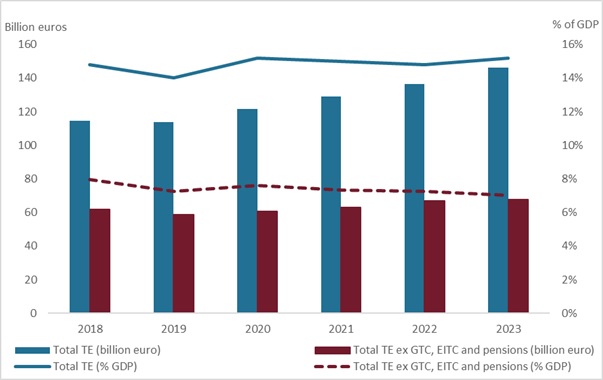

As a result, the spotlight on the country’s tax expenditures continues to intensify. Scale and scope are significant. The country’s annual budget for 2024 lists 122 different tax expenditures. The total revenue forgone from these provisions is estimated at 163 billion euro, or 15% of GDP (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total costs of tax expenditures in The Netherlands

Source: Own elaboration, based on the TE report in the Budget 2024.

This figure is significantly higher than in other countries, but this is due up to a large extent, to the size of the general tax credit (GTC), the earned income tax credit (EITC) and the treatment of pension savings. That’s why the Ministry of Finance also shows the figures leaving out these three very large TE provisions[2]. In that case the fiscal cost of tax expenditures in the Netherlands amounts to 8% of GDP, more in line with other countries. According to the Global Tax Expenditures Database (GTED), the global yearly average lies around 4% of GDP, and has been stable around that figure for the 1990-2021 period covered by the GTED.

The budget also provides information on ongoing and completed evaluations of tax expenditures. Following the Budget Regulations, every tax expenditure has to be evaluated every 5 to 8 years.[3] The government sends this information to the parliament, sometimes along with proposals to abolish or adjust a specific tax expenditure provision.

The quality and scope of tax expenditure reporting in the Netherlands is reflected in the recently launched Global Tax Expenditures Transparency Index (GTETI), where the country ranks 3 out of 104 assessed countries. The key questions are: what does the parliament do with this information and proposals, and what is the real impact on taming the use of tax expenditures?

Budget rules

The current administration introduced a new budget rule on evaluations. The rule prescribes a clear policy reaction to ineffective or inefficient tax expenditures.[4] The basic principle is that in case of a negative evaluation, a tax expenditure must be abolished, cut back or converted into a subsidy. If there is political will to maintain a negatively evaluated tax expenditure, the responsible minister must explain the rationale behind that decision in the Council of Ministers.

Converting a tax expenditure into a subsidy increases the financial incentive for the line ministry to control it, since direct subsidies fall under the expenditure cap and the ministry needs to compensate any overruns. In contrast, only fluctuations in tax revenues that are a direct result of tax policy changes have to be compensated. As a result tax expenditure overruns don’t have to be compensated.

Whereas the new rule on negative evaluations introduced by the current administration is likely to have an impact at taming the use of tax expenditures, there is still an important level of discretion regarding how the cabinet and, subsequently, the parliament deal with negatively evaluated tax expenditures. The tax-free allowance for foreigners working in the Netherlands (the “30% facility”) and the reduced excise tax rate for small beer brewers are cases in point.

The 30% facility

Employees from another country who come to the Netherlands to work often receive reimbursement for the additional costs of that stay outside the country of origin, known as extraterritorial costs. Employers can choose how to reimburse these costs in the first years: reimbursement of the actual extraterritorial costs tax-free or applying the 30% rule under certain conditions.

Under the 30% rule, foreigners who migrate to the Netherlands for work reasons can be paid 30% of their salary tax-free provided that the salary (in 2023) exceeds 41,954 euro per year (not including the tax-free allowance). This provision should compensate for the additional costs of living outside the country of origin for the first 5 years[5]. It is also more simple for the employer and the Tax Authority, as no receipts of all actual costs have to be shown. The income threshold stems from the goal of using the scheme to attract mostly highly qualified workers to the Dutch labour market. In addition, the place of origin of the worker must be more than 150 km from the Dutch border.

In 2016, the Dutch Court of Audit (an independent and non-partisan institution) concluded that the effectiveness of the scheme was unclear[6]. It also highlighted that an annual overview of the fiscal cost of the provision was lacking. A motion was then passed in parliament calling on the cabinet to reconsider the scheme.

As from the 2017 budget, the yearly cost of the scheme, estimated at that time at 900 million euro, is published in the annual review of tax expenditures. An evaluation of the scheme was also conducted in 2017 by the independent research firm Dialogic.[7] The evaluation concluded that the 30% facility was effective and efficient. This outcome has recently been confirmed by a study of the Tinbergen Institute: the 30% facility is effective in attracting skilled migrants to the Dutch labour market.[8]

Yet, Dialogic also suggested that several improvements could be made to increase the efficiency of the provision:

- Shortening the duration from 8 to 5 or 6 years would increase efficiency, while keeping the scheme effective. The report concludes that only 20% of the foreign workers stay more than 5 years in the Netherlands. Within this group a substantial proportion will settle in the Netherlands for more than 8 years or even structurally. The additional positive effects on the decision to come to The Netherlands of a scheme that lasts more than 5 years, are expected to be small. Moreover, in most other European countries these kind of schemes have a duration of 5 years or less.

- Increasing the 150-km limit would also increase efficiency without a significant effect on the number of skilled migrants joining the Dutch labour market. The Dialogic report showed that workers from countries like Germany and France who live more than 150 km from the Dutch border still have relatively low travel costs and other costs of living abroad.

- Reducing the 30% benefit for incomes above 100,000 euro would increase efficiency as the real cost for this group is most likely (much) lower than 30% of their income. Yet, there would possibly also be an effect on effectiveness since workers with an income between 100.000 and 500.000 euro consist, up to a large extent, of a group with particularly high-skills, and hence will likely have alternatives to find a job elsewhere.

The government adopted one of these improvements in the coalition agreement in 2017. In the budget sent to parliament, it proposed to reduce the duration of the scheme from 8 to 5 years, starting in 2019. The measure was to be applied both to existing as well as new foreign employees. This would have reduced the annual cost of the provision, by about 300 million euro.

Several parliamentarians criticized the reduction of the duration, and particularly its backdated nature since, they argued, foreign workers had come to the Netherlands planning on a 8-year tax benefit. As a result of this push-back in parliament, the cabinet introduced a transitional arrangement for existing cases for the years 2019 and 2020. The decision eliminated the 600 million euro in cost savings for those two years, but secured the structural savings moving forward.

The Dialogic evaluation also showed that, for many users (especially for higher income earners), the 30% facility offered a higher compensation compared to what the reimbursement based on actual costs would have been. Hence, the current administration proposed to cap the beneficiaries to earners with annual wages up to 235,000 euro as from 2024. This is equal to the maximum remuneration in the public and semi-public sector defined in the Standards for Remuneration Act.[9] Workers earning more than 235,000 euro can get a reimbursement of 30% of this amount, which caps the reimbursement at 70,500 euro. The savings were estimated at 26 million euro in 2024, rising to 88 million euro a year as from 2026. While some parliamentarians tried to push down the threshold even further (to 100,000 euro), the proposal of the cabinet was finally approved by the parliament.

Prior to these measures, the fiscal cost of the 30% facility had risen sharply, but was invisible to parliament for a long time. Only when the rising costs became more visible with the audit in 2016, and evaluations flagged potential issues with respect to its effectiveness and efficiency, the cabinet and parliament felt the pressure to improve the provision. Eventually, as observed in Figure 2, the two adjustments highlighted above significantly reduced the costs in 2021. But in later years the costs of the facility rose again due to a higher inflow of foreign workers.

Figure 2. Fiscal cost of the 30% facility, in million euro

Source: Own elaboration, based on the TE report in the Budget 2024.

The Small Breweries Provision

Beer brewed by small independent breweries in the Netherlands, i.e., breweries with an annual production of less than 200,000 hectoliters, is currently taxed at a reduced excise rate. The reduction is 7.5% of the standard rate. The revenue forgone is estimated at about 2 million euro per year.

Under the tax system in place before 1992, with a levy on wort, small breweries had a reduced excise rate. The original idea was that smaller breweries operate less economic and would therefore, with a uniform rate, end up with a higher effective rate than the larger breweries. After the tax system changed in 1992 to a levy on the end product beer, instead of wort, small breweries were effectively taxed the same as large breweries. The rationale for the reduced excise rate for small breweries had disappeared. However, for political reasons, namely to make the transition to the new tax system as smooth as possible, it was decided to keep the reduced excise rate for small breweries in place.

A 2008 evaluation concluded that the rationale for the provision had lapsed as of 1992 and, thus, the scheme was, by definition, ineffective. Yet, the Small Breweries tax expenditure provision is still up and running.

In the 2022 budget, the government proposed to abolish the provision by 2023. It also put forward a transition to alcohol content as the tax base for the excise duty, in line with a European regulation. Whereas that transition was designed to be budget neutral, it would have negatively impacted high alcohol content beers, which are often beers from small breweries.

When the bill was debated in parliament, the cabinet encountered considerable resistance. This was fuelled by the powerful lobby of the small breweries. One parliamentarian asked, “Who instructed the Deputy Minister to come up with regulations that nearly wipe out an entire industry?”. Another member of the parliament highlighted the role of “… small, locally oriented entrepreneurs, who sometimes brew beer more from a love of the craft than from commerce. They often brew a beer that represents the pride of their area, which the community in turn is proud of.”

Sentiment in parliament against abolishing the reduced rate for small brewers was broad-based, despite its obvious lack of effectiveness. It was also explicitly stated that “the budgetary savings were relatively small”. An amendment to the tax bill to reverse the abolition of the reduced rate and, at the same time, postpone the transition to the new tax base from 2023 to 2024, was passed by 144 votes to 6.

Conclusions

The two examples discussed before show two things.

First, the concrete design of tax expenditures matters significantly. Whereas the spirit of the 30%-facility stayed unchanged (foreign high-income employees continued to receive a tax benefit to relocate to the Netherlands), based on the evaluation some adjustments to the provision were made which did modify some of its design parameters. This had a large positive impact on public coffers. This is welcome at times of reduced fiscal space, and when both the administration as well as the parliament have to make budgetary choices. This may explain why the parliament ultimately passed the proposed adjustments, albeit slightly modified.

Second, while simplification of the tax system is an important goal, it may run counter to the much broader set of objectives policymakers pursue. In the case of the small beer brewing provision, sentiment and protectionist statements played an important role. This said, the potential savings of the reform would have been minimal: 2 million euro, compared to a total revenue of 466 million euro from excise duties on beer, which can explain, up to a large extent, why the objective of simplifying the tax system was ignored in this case.

[1] Ministerie van Financiën, “Ambtelijk rapport aanpak fiscale regelingen”, 2023

[2] The General Tax Credit applies to all taxpayers and could be seen as part of the baseline tax system. The EITC and the provisions for pension savings apply to 90% and 75% of all workers.

[3] These Budget Regulations provide guidelines to the ministries on how to handle their budgets and are based on the Accounting Law. They apply to all ministries and are adjusted every year by the Ministry of Finance. Only in special cases and with permission of the Minister of Finance deviations from these regulations are permitted.

[4] The Cabinet Budget Rules are agreed upon at the beginning of each administration, and apply for the whole cabinet period of 4 years. They contain guidelines on how ministers have to deal with (unexpected) developments or new political priorities with budgetary implications.

[5] As from 2019 for new workers. Before 2019 the maximum duration was 8 years.

[6] Algemene Rekenkamer, Fiscale tegemoetkoming voor experts uit het buitenland: de 30%-regeling, 2016

[7] Dialogic, Evaluatie 30%-regeling, 2017.

[8] L. Marie Timm, M. Giuliodori, P. Muller, Tax incentives for high skilled migrants: evidence from a preferential tax scheme in the Netherlands, Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper, 2022.

[9] As the amount is indexed annually with wage growth in the private sector, the figure for 2024 is an estimate.